Próba wiary „Musimy porozmawiać o Kevinie” Lynne Ramsay

Mathias Foit

Student Instytutu Filologii Angielskiej Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego (pod kierunkiem dr Justyny Deszcz-Tryhubczak)

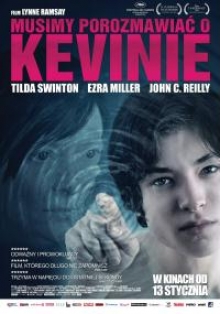

Błyskotliwe i ironiczne hasło plakatowe promujące film Lynne Ramsay z 2011 r., „Musimy porozmawiać o Kevinie” – „mały potwór mamusi” – dostarcza widzowi sprytną wskazówkę na temat sposobu przedstawienia dzieciństwa i młodości w tym obrazie. Od momentu narodzin Kevin (grany przez trzech różnych aktorów z Ezrą Millerem w roli nastoletniego Kevina) jest utrapieniem dla swojej matki – pisarki i podróżniczki Evy Khatchadourian (Tilda Swinton). Gdy jest niemowlęciem, płacze godzinami; gdy stawia pierwsze kroki, odmawia zabawy i komunikacji werbalnej; a gdy jest kilkuletnim chłopcem, rozbryzguje farby w gabinecie swojej matki i umyślnie robi kupę w pieluchy, których nie przestaje nosić nawet w nienaturalnie późnym wieku. Mąż Evy, Franklin (John C. Reilly), wydaje się być ślepy na coraz bardziej antysocjalne, złowieszcze zachowanie swojego syna i krytykuje żonę za jej uprzedzenia. Nawet po narodzinach drugiego dziecka, Celii, Eva pozostaje osamotniona w roli przerażonego obserwatora postępującej socjopatii jej syna.

Oparty na powieści Lionel Shriver film przyjmuje perspektywę narracyjną literackiego pierwowzoru; wydarzenia przedstawione są z punktu widzenia Evy. Nie mogąc pogodzić się ze swoją przeszłością i ostracyzmem ze strony swoich sąsiadów, bohaterka wspomina kluczowe momenty prowadzące do jej separacji z synem i życia w samotności. Powtarzająca się w filmie zapowiedź nieuchronnej tragedii spełnia jeszcze jedną funkcję – tworzy napięcie i dramaturgię. Wzmacniają je wszechogarniająca cisza i brak muzyki instrumentalnej oraz wszechobecna czerwień, którą Eva bez przerwy zmywa ze ścian swojego domu; prawdopodobnie w próbie wymazania przeszłości i odpokutowania win syna.

Krytycy zgodnie nazwali „Musimy porozmawiać o Kevinie” thrillerem psychologicznym. Istotnie, jego niepokojący portret dzieciństwa i młodości oraz przerażające czyny Kevina uzasadniają użycie tego terminu. Film posiada także trudny do zignorowania aspekt filozoficzny; centralne pytanie, które Eva zadaje pod koniec filmu – dlaczego? – nie ma jednej rozstrzygającej odpowiedzi. Czy to wrodzoność zła? Albo rezultat ambiwalentnego stosunku Evy do macierzyństwa, który zresztą został wymieniony przez Shriver jako jeden z kluczowych motywów powieści [1]? A może jest w nas dość optymizmu, by zobaczyć w Kevinie człowieka, a nawet współczuć mu, gdy wyraża wyrzuty sumienia za to, co zrobił? „Musimy porozmawiać o Kevinie” to test wiary. Bez względu na odpowiedź, którą wybierzemy, jezuicki duchowny i krytyk filmowy Jake Martin przekonuje, że zwieńczeniem filmu jest „zbawienny morał”, prawdopodobnie na temat ludzkiej zdolności do przemiany [2]. Czy wierzymy w przemianę Kevina?

Na pewno powinno się o tym chłopcu rozmawiać. Film tworzy niepokojącą wizję dzieciństwa potwornego, a Kevin Khatchadourian z pewnością dołączy do filmowego panteonu demonicznych dzieci. Tworząc napięcie godne Alfreda Hitchcocka, „Musimy porozmawiać o Kevinie” zasługuje na słowa pochwały zarówno jako thriller psychologiczny, jak i film w ogóle.

The witty and ironic slogan on the poster of Lynne Ramsay’s 2011 film „We Need to Talk About Kevin”, „Mummy’s Little Monster”, gives the viewer a smart hint about its portrayal of youth and childhood. From the very moment of his birth, Kevin (played by three different actors, with Ezra Miller as the teenage Kevin) is a nuisance to his mother, the travel writer Eva Khatchadourian (Tilda Swinton). As an infant, he screams for hours on end; as a toddler, he is reluctant to play and communicate verbally; as a young boy, he vandalises his mother’s study with paints and deliberately poops in his nappies, which he continues to wear until an unnaturally late age. Eva’s husband, Franklin (John C. Reilly), seems oblivious to his son’s increasingly unsocial and malicious behaviour and rebukes his wife for her prejudice. Even after giving birth to a second child, Celia, she remains abandoned as the terrified witness to her son’s alarming sociopathy.

Based on a novel by Lionel Shriver, the film adopts the source text’s point of view; the story is presented from the perspective of Eva: unable to come to terms with her past and the ostracism she suffers from her neighbours, she constantly recalls the key events leading up to the estrangement with Kevin and her life of solitude. The film’s recurrent foreshadowing of the tragedy that is to come serves yet another purpose — that of creating suspense and dramatic tension. It is strengthened by the pervading silence and lack of instrumental music, as well as by the ubiquitous colour red that Eva constantly tries to wash off the walls of her house—probably in an attempt to erase her past and atone for her son’s actions. „We Need to Talk About Kevin” has been consensually called a „psychological thriller” by critics; indeed, the disturbing portrayal of youth and childhood as well as Kevin’s horrifying behaviour substantiate the use of the term. The film also possesses a philosophical aspect that is hardly dismissible; the film’s central question that Eva asks by the end of the film, that of „why?”, does not lend itself to a straightforward answer. Is it the innateness of evil? Or maybe the consequence of Eva’s ambivalence towards maternity, which Shriver pointed out as one of the central themes of the novel? Or are we optimistic enough to see the human side in Kevin and even sympathise with him as he expresses remorse for what he has done? „We Need to Talk About Kevin” is a test of faith. Whichever alternative one chooses, the outcome of the film, according to the Jesuit priest and film critic Jake Martin, is a „redemptive message”, probably about the human potential for transformation. Do we believe in Kevin’s?

He should definitely be talked about. The film creates a disconcerting vision of a monstrous childhood, and Kevin Khatchadourian is bound to join the film pantheon of demonic children. Creating tension worthy of Alfred Hitchcock, „We Need to Talk about Kevin” certainly deserves its praise as a psychological thriller and as a film in general.

Przypisy:

[1] Jenefer Shute, „Lionel Shriver”, „BOMB Magazine”, Jesień 2005. 26 grudnia 2015.

[2] Jake Martin, „Musimy porozmawiać o ‚Musimy porozmawiać o Kevinie'”, „Busted Halo”, 23 grudnia 2015.